When You Are a Victim: What the System Expects From You (and What It Owes You)

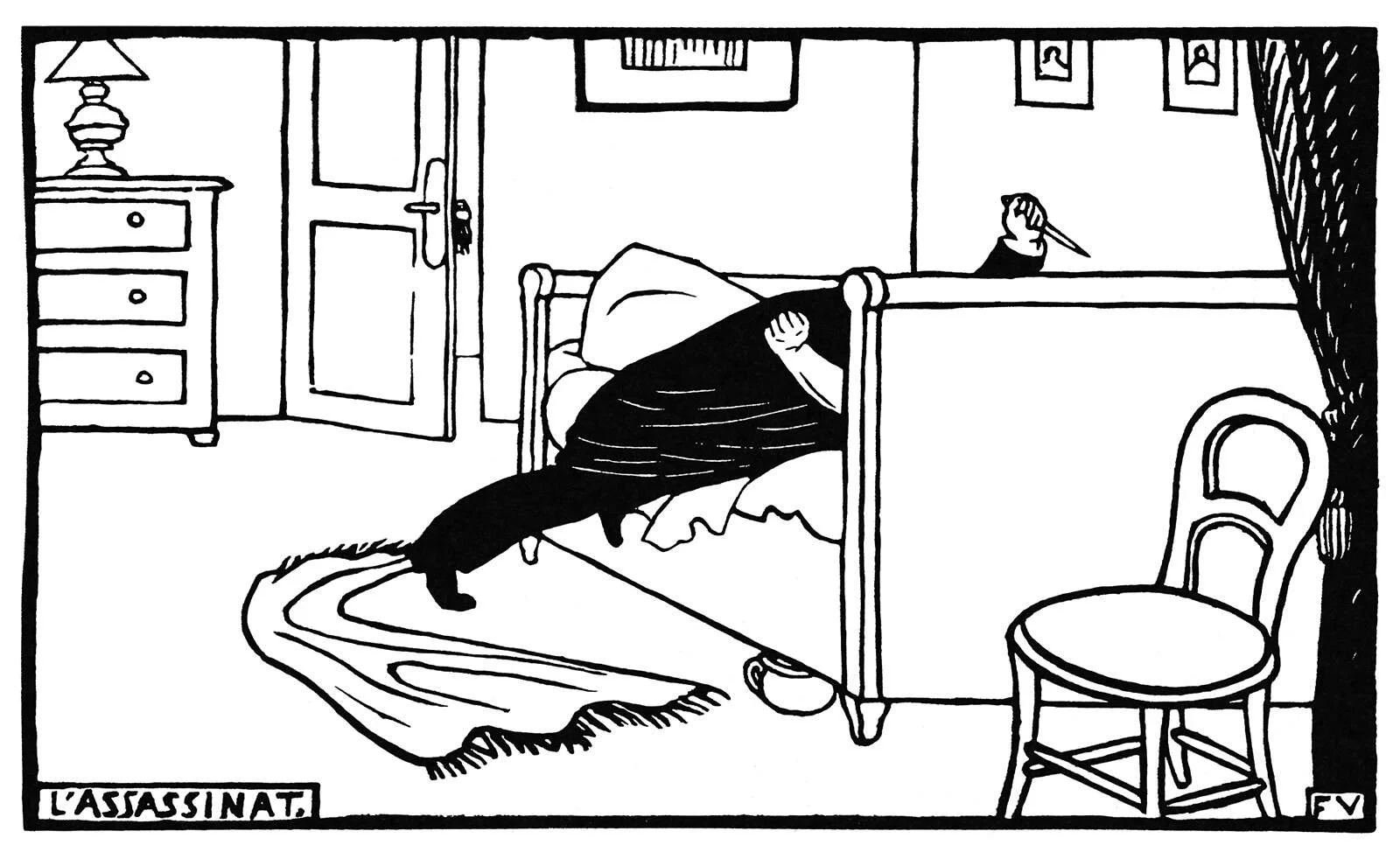

Berlin, Paris: Edmond Sagot, J. A. Stargardt. Félix Vallotton; biographie (1898) Woodcut by Félix Vallotton. https://archive.org/details/gri_33125000519179/page/n149/mode/2up (page 150 / 172)

Being a victim of a crime is difficult. Beyond the emotional toll, there is a legal system to navigate, and many victims feel lost or unsure of what comes next. It is common to hear people say, “Just report it to the police and everything will be taken care of.” The reality is more complicated. Understanding what the system expects of you, and what it owes you in return, can make the process less overwhelming and, importantly, less disillusioning.

The legal system is not designed around healing. It is designed around proof. Its primary objectives are to gather evidence, establish facts, and determine responsibility under the law. Police investigate. Prosecutors assess whether the charges should be filed and sustained - this means a consideration of whether the evidence collected fulfil the legal ingredients of the offence (and not merely what we think is the crime), and even if the evidence is adequate, whether it is in the public interest to prosecute. Courts evaluate evidence against legal standards. Within this structure, the victim is often the starting point, but rarely the focal point. The complainant makes the report to the authorities - he or she may or may not necessarily be the victim of crime. A complainant may be a person who witnessed the crime, someone who (never mind hearsay) received information of the offence, perhaps a guardian or employer of the victim or offender. I was assigned to represent a man who admitted to taking the life of his lover and then he brought the body to the police station complete with all the evidence and the “murder weapon” as was revealed in the course of trial. In that case the complainant was the offender. He was found guilty by the High Court and the Court of Appeal upheld the decision. At the date of this writing, his appeal due for hearing next month before the Federal Court.

What the system expects from you is consistency, cooperation, and restraint. You are expected to give a clear account of events, to repeat that account when required, and to submit to procedures that may feel invasive or unnecessary. You may be asked why you did not act differently, why you delayed reporting, or why certain details were omitted earlier. These questions are not always asked with sensitivity, but they are asked because inconsistencies weaken cases. The law values reliability more than emotion, even when emotion is justified. I have been approached by victims and their families who observed long waiting hours at the Balai or IPD, last-minute rescheduling of meetings with the IO, being subject to repeated questioning of the same thing again and again. Some experts found that this repeated questioning can cause a form of secondary re-traumatising for the victims and their caregivers. Thus I do hope that our dear friends in the investigation departments take heed: economise and plan the investigation according to procedure and best practices. That being said, I have come across some efficient investigators and SIO who supervised their AIO with the benefit of experience.

This expectation of consistency, cooperation, and restraint creates a significant risk for victims. Memory is not static, particularly after trauma. Details surface later. Timelines blur. Emotional responses do not always align with what investigators expect from a “credible” complainant. Victims often fear that a single mistake in wording or recollection will undermine their entire case. This fear is not irrational. Credibility assessments matter, and victims are acutely aware that they are being evaluated, not only heard. A notebook with notes jotted soon after the incident would be valuable as an aid to memory recollection and to guide the investigator on certain points. Nowadays, people seem to like to store notes on their smart phone device or even send a WhatsApp to themselves containing such notes. Due to the nature of such information and storage, it is advisable to have it down in hardcopy. Many investigators are emphatic, compassionate and dutiful, but there are bad apples who do a disservice to the police force and the victims with poor attitude, failure to observe proper police procedures, lack of creativity and maturity in handling a case, and importantly, poor communication with victims and other stakeholders. This does not reflect on all of the police force as many do perform their duties with pride.

Society reinforces this pressure upon victims. Victims are expected to be cooperative but calm, affected but not emotional, assertive but not angry. When they deviate from this narrow range, they risk being doubted or dismissed. Public narratives about false reporting, exaggerated claims, or ulterior motives contribute to an environment in which victims feel they must constantly justify their own suffering. This is compounded when they are put to task in court to explain why they delayed making their police report!

Tragically the victim took her own life when police did not proceed with the case. More at the link : https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2956542/Mother-killed-day-learning-police-dropped-probe-claims-raped-sex-offender-NHS-clinic.html

One of the most difficult realities for victims is continued interaction with suspects, directly or indirectly. Reporting a crime does not always result in immediate separation. Suspects may live nearby, work in the same community, or share social circles. In some cases, they may attempt to contact the victim under the guise of explanation, apology, or reconciliation. In others, the contact is overtly intimidating. In cases of domestic violence, the Domestic Violence Act 1994 provides for the Interim Protection Order (IPO) that can be custom-designed to temporarily protect the victim, or at least to deter the suspect, during the course of investigation, so that the victim can have some breathing space and the investigation can proceed without tampering of witnesses.

Even when the suspect does not engage directly, pressure may come from family members, friends, or associates of the suspect or even the victim. Victims may face harassment, gossip, or social isolation. They may be blamed for causing trouble, accused of exaggeration, or urged to withdraw their complaint for the sake of peace. These actions are rarely recognised as part of the harm, yet they can be as destabilising as the original offence. In my humble view, the pressure to withdraw the report for the sake of peace is common. Peace in this context may mean to protect the reputation of a family from being violated by the outside world. Or the reputation of a company where the livelihood of other employees are at stake. Or a school where bad press could have unpredictable and uncontrollable effects upon the other innocent school staff, other students and parents. What ever this objective of peace, anecdotally this is also seen to be a convenient cover to sweep the problem under the carpet. It suppresses the suffering of the victim. It denies justice. It sends the wrong message to the other people involved in the case. As much as we are concerned that the suspects or their families would use corrupt means to bring about this “peace”, we should eventually be concerned that the victim and their families pursue justice outside the legal framework where lawful means have failed. It could be said that actual perpetrators are more likely to bet on nothing happening if the case is suppressed.

The law often struggles to respond to this reality. Protective measures exist, but they usually require additional reporting, additional evidence, and additional resilience from the victim. Many victims hesitate to escalate matters, fearing they will be seen as difficult or uncooperative. Others simply do not have the emotional capacity to keep pushing. The investigation of a crime can sometimes be or nearly be as traumatising as the actual crime. It is often a lonely journey where the pain of a victim remains unseen. Air mata jatuh ke dalam, orang lain tidak tahu.

I touched on this above. Interactions with investigators can also present obstacles. While many officers are professional and committed, victims sometimes encounter dismissive attitudes, rushed interviews, or a lack of follow up. This may stem from workload pressures, limited resources, or unconscious bias about what constitutes a serious case. For the victim, however, the impact is the same. They feel unheard, minimised, or treated as an inconvenience rather than a person seeking justice.

It is important to understand that dismissal does not always mean disbelief. Investigators are trained to prioritise cases based on evidence and legal thresholds, not moral weight. Still, when communication is poor, victims are left to interpret silence or brevity as indifference. This erodes trust and increases the likelihood that victims disengage from the process altogether.

What the system owes victims is not a guaranteed outcome, but procedural fairness and respect. This includes clear explanations about what can and cannot be done, timely updates, and honest assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of a case. It also includes recognising the secondary harms victims face during the legal process, from social backlash to ongoing fear.

Engaging legal advisers or victim support services can help restore some balance. These professionals act as intermediaries, translating legal language, setting realistic expectations, and advocating where possible. In Malaysia, only a practising advocate & solicitor is permitted to provide legal advice for a fee. However, free legal aid is also provided by certain lawyers, NGOs and Jabatan Bantuan Guaman. They can also validate concerns that the system may not formally acknowledge, reminding victims that difficulty navigating the process is not a personal failure. Validation is a sensitive subject, so I think licensed counsellors would be better placed to handle this as part of the recovery and rehabilitation process for victims.

Being a victim means carrying a burden you did not choose, within a system that was not designed with your comfort in mind. The law asks you to be precise when you may feel fragmented, patient when you feel urgent, and composed when you feel exposed. In return, it owes you transparency, dignity, and protection within its limits.

Justice is not only about outcomes. It is also about process. When victims understand both the constraints of the system and their place within it, they are better equipped to protect themselves, assert their rights, and endure a process that often demands more than it acknowledges.